Education In Albania Today

A special interview with an Albanian English teacher helped me understand that educational systems have amazing similarities and differences.

ALBANIA

9/18/20255 min read

From a personal lens, I spent 47 years in the American public school system as a student, as a special education teacher, and as an instructional coach. I consider myself an expert on “School” and would attempt to answer any of your questions. However, I was introduced to a public-school teacher in Pogradec, Albania and my entire perspective of “School” suddenly shifted.

First, you need an introduction with numbers. I met Gina (pronounced Gw-ee-na) at a social meet-up and asked to interview her. Gina is a mom in her 40’s who has been teaching English in Albania for 8 years. She works with students in the 1st through 9th classes. To become an educator in Albania she spent 3 years earning her bachelor’s degree and 2 years earning her master’s degree. Both are required to obtain licensure, and all teachers today must have courses across the entire instructional spectrum (reading, writing, math, listening, play, etc.). Albania teachers cannot specialize their teacher prep pathway (math-science or even elementary-secondary). A teacher is a teacher, and THE teaching degree is valid for every classroom.

Second, you need the framework. Today, school in Albania is compulsory beginning at age 6 with some 5 ½ year olds allowed. There are city school buildings and village school buildings. Public school is separated into two structures, grade level 1st-9th and then high school. Levels 1-9 have curriculum books provided by the Albanian government, but high school books must be purchased by families as students start planning for their future pathway. The cost for the family is about $50.00 per year. There are private schools at all levels too, but they can be much too expensive for some families.

The public-school year operates from the beginning of September to the middle of June with a winter holiday (December to January) and a spring holiday (March to April). Students attend classes on a Monday through Friday schedule from about 08:00-13:30 daily. Elementary age students learn for 2-hour chunks, then take a break. Older students learn in 3-hour chunks before their break. During their breaks they can eat, use the toilet, or have organized play.

The government mandates a minimum of 10 students and maximum of 29 students per classroom at all levels. Many families have moved out of Albania which is impacting current class sizes, and sometimes there are not enough students to fill a class. So, it’s not unusual to have a classroom in smaller towns with a combination of 1st level mixed with 5th level students or even three grade levels in one classroom. The teacher then breaks the students into instructional groups based upon their level. All students, even those with different learning abilities, receive instruction in their one classroom with one teacher except for physical education. Therapy for speech or motor skills are not provided in the Albanian school setting. There are no school buses and no lunch program. Parents who live in villages may choose to transport their children into the city or they can have instruction in the village, which may require an itinerant teacher. Students accessing the city school instruction happens more often at the high school level.

Third, you might be curious about teacher assignments and compensation. When Gina finished 5 years of college and received her license, she had no guarantee of her dream job for teaching. Positions in city schools and village schools must be filled, and the number of positions is dependent upon enrollment. While some teachers may get a permanent position, many English teachers are itinerant. Imagine the system like a lottery. Each year in July, Gina and her fellow teachers must take a placement test. The results of the tests are compiled by rank and positions are offered in August via an e-mail list from the regional Teacher’s Offices. Gina is enrolled in the Pogradec and Korcë regions.

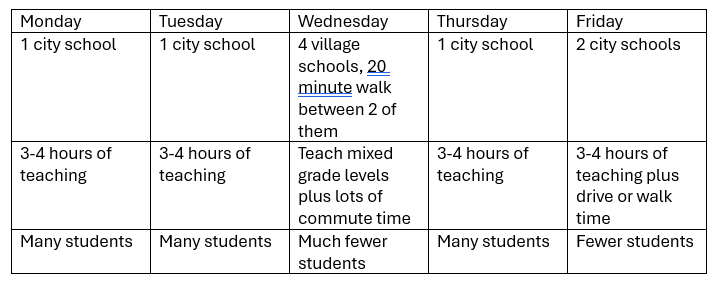

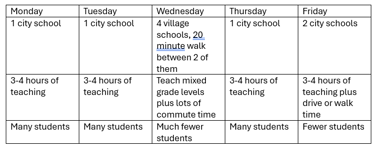

If the school year begins on 8 September, and Gina was not given her new assignment in August, then she must wait until 5 September when the student numbers are confirmed before she learns the locations of her new schools. She may be assigned to city schools or village schools, or both. Some of the village schools are 3-4 hours away from her home, which can make for long days away from her family and a less desirable assignment. Thankfully, the curriculum tends to be consistent, and she does not need a lot of prep time for the new school year. An example of Gina’s weekly work schedule might look like this.

Fourth, you may wonder about student discipline and parents. From the lens of the older generation, a student was considered “naughty” if they did not work hard enough. As the generations evolved, “naughty” might look a different now, but schools in Albania are not facing the physical aggression from children that might be seen in other countries. Students who require some discipline might be sent out of class for 10-20 minutes, their parents may be contacted, or they may have to talk with the director. A psychologist may be contacted to support emotional needs.

There are times when an Albanian teacher must share difficult information with a parent about a student’s performance. Not all parents understand why their child is not successful in school. Some parents blame the teacher for not instructing well enough. Questions may arise about homework time and then the teachers find out that parental oversight or help with homework is not happening. These conversations can be uncomfortable for all parties.

Gina and her colleagues report to a regional director/assistant director. Those directors report to the director of the Albanian Education system. Each regional director requires teachers to submit diaries related to the daily instruction. Gina is expected to submit her diary at the end of each school day, but some directors require them weekly or monthly. This diary used to be handwritten but now is submitted via computer.

Gina is paid by the school system once per month. After 8 years of teaching, her compensation is nearly $700.00 per month. All teachers are on the same salary with advances at 5 years, 8 years, 12 years, and 20 years. If Albania joins the European Union, which it is vying for, then the salaries may increase significantly.

Finally, as I was wrapping up my questions with Gina, I wanted to understand her perspective on two final questions.

1. What do you find challenging with the Albanian school system? After thinking a moment, Gina explained that the politics which swirl around the educational system can be difficult to negotiate, but more impactful are the missing tools for the students. Teachers do what they can to purchase necessary items which help students learn, but the lack of balls, technology, and classroom tools can impact the quality of education.

2. What are you most proud of in the Albanian school system? Without hesitation, Gina answered. Most Albanian students want to learn. Even if they find school challenging, like her own nephew, they work hard and find successes. The Albanian students even find success on the international stages.

**This article is dedicated to all the wonderful and hard-working teachers I know in America and Albania. Education has great challenges, but also great rewards. I personally want to thank Gina for sharing her time with me over coffee in Pogradec.